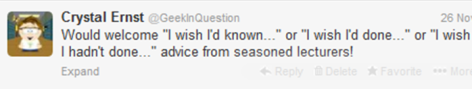

The grades are in, and as promised I’m going to take some time to talk about my experiences as a first-time teacher. Long story short: it was super-challenging and I loved it.

Where the magic happened…

I put together a list of ten important things I learned this term; I hope others find these useful, and I welcome any feedback or comments!

1. No matter how confident you are, when you’re given your first class you’re probably going to be freaked out at some point. Do whatever you need to do to get through the first few lectures – it gets easier.

I love teaching, and I consider myself a good teacher. Nevertheless, in the weeks leading up to the start of the term as I tried to prepare my first couple of lectures, I had many sleepless nights and about five mini-breakdowns during which I decided I was woefully unqualified and couldn’t figure out why on earth I’d been asked to teach this course (Math? Me? Aaak!)

I really over-prepared to try to compensate for these feelings. I had hand-written notes, which I then transcribed to type-written, which I then transcribed again into my official class notebook. (Because practice makes perfect?)

Yeesh.

These carefully crafted notes, which took me days (no, let’s be honest: weeks) to produce, lasted all of three or four lectures. In hindsight, it was a good confidence booster even if it was overkill. I knew exactly what I wanted to cover and how I wanted to cover it – I had, for all intents and purposes, a script. This was especially useful for the first few days because I was a nervous wreck and having a clear, well laid-out plan made things easier.

But, a) the time investment per lecture was simply unsustainable, and b) after a few lectures I realized that I was not exactly incompetent and the classes were going well. So I chilled out, got comfortable with prepping my lectures only a day or so in advance, and grew confident in my ability to ad lib.

2. It’s going to take way more time than you think.

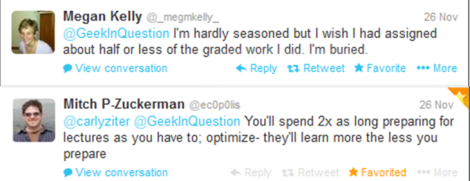

If you ask for advice, as I did, people will tell you: “three hours of prep for each hour of lecture”. LIES. Lies, lies, lies. If this is the first time you’ve taught a course it’s going to take a lot more than that unless you’ve literally been handed a set of PowerPoint slides and a script. (And really, would you want that? Yech.)

Reading, learning the material, finding supplemental literature/examples/activities, preparing slides or notes, managing online spaces and uploads, drafting tests/quizzes/rubrics, practicing lectures a little bit to smooth out some tricky spots – I figure I spent at least double the basic estimate: probably six hours/hour.

Was this too much? Maybe. I know that I can be a bit perfectionist and REALLY wanted to do well, but it was absolutely the amount of time I needed to spend to feel competent, prepared, confident and have classes that ran smoothly and on time.

3. Take the time to get to know your students.

This means names, background, experience, interests. On the first day of class I handed out cue cards and asked students to write their name, major, previous ecology experience, and a bit about their ecological interests (“what is your favourite part of nature?”) I then printed, cut out and glued the student’s photographs (these are available to instructors at my school) on the back of the cards. These became little flashcards I could use to quiz myself when I had a few spare minutes (on the bus, making breakfast, between sets during a workout) – to match the face with the name. I didn’t get them all – I’m really bad at remembering names – but this technique worked better than anything else I’ve tried to date.

In addition to names, I got a sense of what the students were interested in – lots were keen on forests, big predators and coral reefs. When I prepped my lectures I would look for examples that touched on many of the different themes, systems or organisms listed on these cue cards – it helped students make links to topics with which they were already familiar and in many cases seemed to enhance the quality of our discussions because they had opinions, experiences and prior knowledge to contribute.

We also did a group assignment, and I used the cards to assemble groups that united people with shared interests, and promoted diversity in terms of level of experience or major.

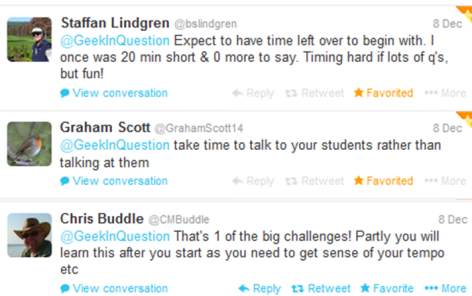

4. Figure out what kind of learning environment you want to create: set the ground rules and expectations early and stick with them.

There are a couple of ways to do this. First, spend a lot of time working on your syllabus. Err on the side of “too long”. It’s a contract – you lay out your expectations of your students, not just in terms of the content/workload, but also in terms of classroom comportment. You should also use the syllabus to tell the students what they can expect of you. It’s only fair, and spares everyone a lot of unpleasant surprises. Consider things like use of tech gadgets in class (cell phones, yay or nay?), turnaround times for email replies, expectations for doing work outside of class, procedures for disputing marks, matters of punctuality, etc.

As a brief example, I told my students that classes would start and end on time. I held up my end of the deal by setting an alarm on my cell phone – at 12:25 the beeper would go off and if I couldn’t wrap up what I was doing in 10 seconds or less I’d cut it off right away. This completely eliminated the usual loss of focus and coat-shuffling/stuffing of notes into bags that usually happens near the end of lectures – students knew they could count on me to let them out on time. It also seemed to encourage them to arrive punctually, or to at least warn me in advance when they’d not be able to be on time, and they demonstrated respect for their classmates upon arriving/leaving by keeping the disturbance to a minimum.

Another thing I strongly recommend is to set the in-class tone on day one. Do you expect students to engage in discussions, do group work, ask questions, solve problems in-class, read from PowerPoint slides, use clickers, take notes from the chalkboard? Have them do these things on the FIRST day of class as much as possible.

I think this is especially important if you are straying from the traditional “I will stand at the front and lecture at you with slides” teaching format that most students are accustomed to. If you plan on employing active or student-centered learning strategies in your class (and you should), you need to make it clear ASAP because you might encounter resistance from some students. They will be able to determine, before the drop/add date, if the class content AND format are going to align with their needs and interests.

5. Develop thoughtful, thorough assignment descriptions and rubrics, and grading schemes for exams.

This will take a fair bit of time, but, a) it’s so worth it, and b) it’s just good pedagogical practice – not just good, but absolutely non-negotiable in my opinion, whether you or a TA are doing the marking. Make the information available to students as early as possible.

Rubrics will make marking a hundred times faster, will all but eliminate inconsistencies or subjectivity in the grading, and will significantly reduce the amount of questions or complaints you get about marks, especially if you provide the exam grading schemes after the exams have been handed back. Students can easily check their own work and figure out where they went wrong, and I’d argue that there’s better learning to be had in that process than a discussion with the instructor.

Part II next week!